Louis Reed

568 Grand St 10002

info@louisreed.nyc

Michaela Bathrick

People

March 24 - April 24

I) Since the onset of Modernity cement has been its literal substance. This material also constitutes the structure of Michaela Bathrick’s continuous, numbered, and systematic works.

II) Modernism is an elusive term, best understood by examining its aspirations and failures. It resisted the bourgeois beast¹ of culture. However, even its most storied institution –the Bauhaus– was swallowed by it.

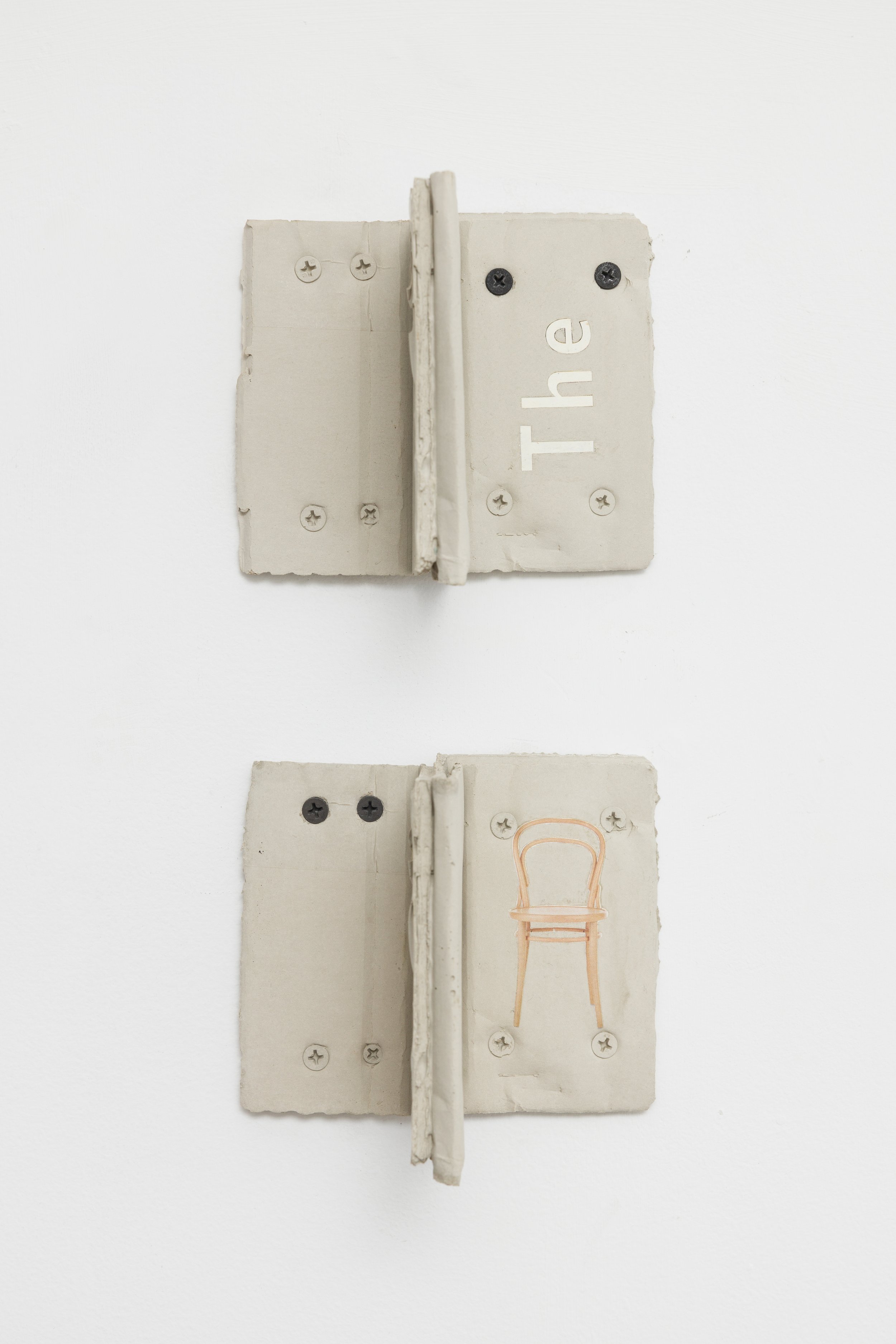

Bathrick's works are compounds of Modernity and Modernism, the material condition of the former and the spiritual residual of the latter. On display are cardboard assemblages cast in cement from silicone molds. These works incorporate inlaid images from the Design Within Reach catalog and People Magazine. The urban reality found in the constructs’ form and material, in conjunction with the sleek, streamlined Mid-Century Modernism designs underlines the odd fit between the elements and the untimed resurgence of Modernism.

Mid-Century Modernism is a predominantly post WWII, American school of thought. It inherits Bauhaus ideals while displaying a greater tolerance of design as a luxury in the context of desire for comfort, individualism, and status through possession. At moments of its history, the era aesthetics has become an endorsed brand, a well-tread path, safe and illuminated. It is contemporary enough to be modern, modern enough to be understood.

Moving forward in time, the very term Modernism is repackaged. This packaging has reached a point where it is about achieving an impression of a false aspiration. The diluted, dim connotation to historical Modernism is the desirable subject for consumption. Seen in this perspective, Modernism has long crumbled. The sensibility, short in supply, that produced early Modernism, is in favor of an unrelenting arrival at a singular, automatic aesthetic experience. A singularity as arbitrary as the numbers the artist assigns in her symmetry: the serial characters set into the surface of concrete, the E, T, u, O, j structures creating bi-fold containments and compartments, the punctuation of the uniform anvils pointing left.

The series Anvil are modeled after Harbor Freight’s blacksmithing tool. The iron is recast in soap, mixing in fiberglass shards and dust, staples and metal filings. The conversion from an artifact of utility to a symbol is made using lye, oil, and water, a technique that has moved from being accessible and commonplace to esteemed and exclusive. Just as these prickly soap anvils evolve in color and composition over time, elite culture may become appropriated by new generations and a utilitarian object or process can attain new status. These value assignments, not unique to Modernism, are the ones that any subject situated within the bourgeois consumer society will encounter.

In a site of Modernity and Modernism, the Cooperative Village on Lewis Street, Playbox I protrudes on the floor of the apartment. The sculpture, a muted obstacle in the main living space, is composed of a toilet, dividing partitions, and a platform with steps in native-gray concrete. It stands bare, devoid of additives — the assimilating strength of the masses and the magnetic power of Modernism — is the first and primal canvas of Bathrick’s.

— Eva Chang

¹Farewell to an Idea, T. J. Clark